Sidney Bloch, The University of Melbourne and Nick Haslam, The University of Melbourne

Possibly the earliest account of a disturbed mind is recorded in a 3,500-year-old Hindu text that describes a man who is “gluttonous, filthy, walks naked, has lost his memory and moves about in an uneasy manner”.

In the Bible’s Old Testament, in the first Book of Samuel, we read that King David simulated madness to gain safety:

And he changed his behaviour … and feigned himself mad in their hands, and scrabbled on the doors of the gate, and let his spittle fall down upon his beard.

In the Book of Daniel, we find a vivid description of King Nebuchadnezzar’s mental state:

And he was driven from men, and did eat grass as oxen, and his body was wet with the dew of heaven, till his hairs were grown like eagles’ feathers, and his nails like birds’ claws.

The ancient Greeks made early attempts to explain madness. In the 5th century BC, Hippocrates viewed it as seated in the brain and influenced by four bodily fluids: blood, phlegm, black bile and yellow bile.

The Greek physician Galen, who practised in Rome 600 years later, argued that depression was caused by an excess of black bile (hence the term “melancholia”, from melan, black, and khole, bile).

His contemporary, Aretaeus of Cappadocia, colourfully described how, if black bile moves upwards in the body, “it forms melancholy; for it produces flatulence and eructations [or, belches] of a fetid and fishy nature, and it sends rumbling wind downwards, and disturbs the understanding”.

A troubled mind, possessed

During the Middle Ages, monasteries preserved the view of madness as an illness, and of those afflicted as sick rather than sinful. At the same time, the more sinister belief that the principal cause of the troubled mind was possession by spirits or the devil prevailed.

Sufferers were taken to sanctioned healers for exorcisms, a practice still carried out today in some cultures. People who failed to respond to such treatment might then seek out a celebrated expert.

Consider Hwaetred, a young man living in what is now England in the 7th century, who became tormented by an “evil spirit”. So terrible was his madness that he attacked others with his teeth and killed three men with an axe when they tried to restrain him. Taken to several sacred shrines, he obtained no relief. His despairing parents then heard of Guthlac, a monk who lived a hermit life north of Cambridge. After three days of prayer and fasting, Hwaetred was purportedly cured.

Wikimedia Commons

Over time, the role of religious authorities in mental illness dwindled, and the medical profession claimed the exclusive practice of the healing arts. Insanity once more came to be seen more as a physical malady than a spiritual taint. Even so, life for the mentally ill could be appalling.

During the 17th century, religiously inspired persecution of the mentally ill was justified by the clerical hierarchy, and treatment was often some combination of neglect and bestial restraint.

Psychiatrists Martin Roth and Jerome Kroll describe the insane in this period as “miserable individuals, wandering around in village and in forest, taken from shrine to shrine, sometimes tied up when they became too violent”.

A watershed: asylums

The late 18th century was a watershed in the history of psychiatry. The insanity of England’s King George III revealed society’s ambivalence to the mentally ill (vividly captured in the 1994 film The Madness of King George).

In France, Philippe Pinel released the chains that had fettered the “lunatic” for centuries, ushering in an unprecedented phase of benevolent institutional care.

Moral therapy, a form of individualised care in small hospital settings, was promoted by English Quakers at the York Retreat and gradually supplanted inhumane physical treatments such as purging, bleeding and dunking in cold water.

As populations grew and urbanised, the sheer numbers of mentally ill people in burgeoning city slums demanded action. An institutional solution emerged.

Asylums (from the Greek word meaning “refuge”) were built in rural settings with the best of intentions, planned to be havens in which patients would receive humane care. In the serenity of the countryside, and through carrying out undemanding tasks, they could be distracted from their internal torment and find dignity far from the bustling crowd.

Daniel Defoe, the English writer, remained unconvinced: “This is the height of barbarity and injustice in a Christian country; it is a clandestine Inquisition, nay worse.”

Although conceived in a spirit of optimism, asylums tended to deteriorate into centres of hopelessness and demoralisation. They soon became overcrowded dumps. Institutions built for a few hundred people were soon holding thousands. Very few residents were discharged; many stayed for decades. Brutal oppression replaced anything that might have resembled treatment; malnutrition and infectious disease became rife.

In the grim environment, people were shut away and forgotten. With them out of sight and out of mind, a loss of public interest and political neglect became the norm.

Wellcome Collection

The brooding building on the hill came to symbolise the stigma and fear attached to mental illness. By the mid-19th century, critics were voicing concerns that asylums had become human warehouses that entrenched mental illness rather than curing it.

The combination of powerless patients, hospitals run more for the convenience of staff than for the benefit of the sick, inadequate inspection by state bodies, and lack of resources led at times to quite disgraceful conditions. Unwittingly, the spread of asylums also triggered the movement of psychiatry away from the mainstream of medicine.

The conditions of the asylums are evocatively described in Henry Handel Richardson’s Australian novel The Fortunes of Richard Mahony. We read of Richard’s decline, probably from syphilis affecting the brain, which at that time afflicted a large proportion of mental patients.

Towards the end of the novel, his wife comes to visit him in the asylum:

She hung her head … while the warder told the tale of Richard’s misdeeds. 97B was, he declared, not only disobedient and disorderly, he was extremely abusive, dirty in his habits … he refused to wash himself, or to eat his food … she had to keep a grip on her mind to hinder it from following the picture up: Richard, forced by this burly brute to grope on the floor for his spilt food, to scrape it together, and either eat it or have it thrust down his throat … There was not only feeding by force, the straitjacket, the padded cell. There were drugs and injections, given to keep a patient quiet and ensure his warders their freedom.

Great and desperate cures

In the asylum, psychiatry turned into a modern medical discipline. The

accumulation of thousands of patients provided the first opportunity

to study mental illness systematically and to develop theories about its

causes.

The idea that these conditions were due to brain alterations, and especially degenerative processes, became dominant, encouraged by the discovery of the cerebral pathology associated with neurosyphilis and Alzheimer’s disease. A similar degenerative process was proposed by the great German psychiatrist Emil Kraepelin to cause dementia praecox – later renamed “schizophrenia” – leading to pessimism about the possibility of recovery.

But the priority for asylums was to relieve the suffering of overwhelming numbers of disturbed patients. Psychiatrists grasped for “great and desperate cures”. Henry Rollin, an English psychiatrist and medical historian, captures the intense zeal:

The physical treatment of the frankly psychotic during these centuries makes spine-chilling reading. Evacuation by vomiting, purgatives, sweating, blisters, and bleeding were considered essential […] There was indeed no insult to the human body, no trauma, no indignity which was not at one time or other piously prescribed for the unfortunate victim.

Treatments were sometimes based on rational grounds. Malaria therapy, for instance, was launched as a treatment for neurosyphilis by the Viennese psychiatrist Julius Wagner-Jauregg in 1917, earning him a Nobel Prize ten years later.

The high fever caused by the malarial parasite disabled the spirochete that caused neurosyphilis, but the hope that it would be equally effective for other forms of psychosis was soon dashed. The wished-for panacea was not to be.

Jimmy Chan/Pexels

Insulin-coma therapy was introduced by Manfred Sakel in the 1930s in Vienna and was soon being used in many countries to treat schizophrenia. An insulin injection was administered six days a week for several weeks, producing a state of light coma lasting about an hour, because of reduced glucose reaching the brain.

Many years later, an investigation carried out in the Institute of Psychiatry in London, a leading research centre at the time, showed conclusively that the coma itself was of no therapeutic value. Any positive change was probably due to the staff’s painstaking care.

ECT and lithium

The first widely available and effective biological treatments for mental illness were developed in the asylum. The discovery in 1938 of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) by Ugo Cerletti and Lucio Bini, two Italian psychiatrists, led to a dramatically effective treatment for people with severe depression.

ECT was eagerly adopted in practice, but its history illustrates a typical pattern of treatment in psychiatry: unbridled early enthusiasm is later tempered by a protracted process of scientific evaluation.

The same can be said of the use of brain surgery to modify psychiatric symptoms. This was pioneered in 1936 by Portuguese neurologist António Egas Moniz (another Nobel Prize winner in the field of psychiatry) and surgeon Almeida Lima, and remains controversial in psychiatry to this day.

A momentous breakthrough was the discovery in 1949 by John Cade, an Australian psychiatrist, of lithium as a treatment for manic excitement. The lithium story reveals how the incorporation of a new medication into psychiatric practice is not always smooth.

Several US and Danish psychiatrists had experimented with lithium in the 1870s and 1890s, only to have their work ignored until Cade’s rediscovery. It was another 18 years before lithium was shown to prevent the recurrence of severe changes of mood, its primary clinical use now.

Major tranquillisers were added to the growing range of psychiatric medications after being discovered fortuitously in 1953. An antihistamine used to calm patients undergoing surgery was shown to reduce the torment of psychotic patients, but without making them sleepy.

Shortly after this, the US psychiatrist Nathan Kline discovered that a drug being tested for its effect in patients with tuberculosis had antidepressant properties — the forerunner of medications for depression. All these drugs radically transformed the practice of psychiatry.

Freud, ‘talking cures’ and shell shock

A very different aspect of mental health care arose in the 1890s, outside

the asylum. Concerned with neurotic conditions, the new treatment grew chiefly out of neurology but was also influenced by a scientific interest in hypnosis and the unconscious.

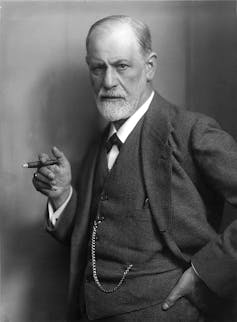

Max Halberstadt/Wikimedia Commons

Sigmund Freud conceived a dynamic model of the mind in which, through the mechanism of repression, painful or threatening emotions, memories and impulses are prevented from escaping into conscious awareness.

Psychoanalysis grew to become an integrated set of concepts about normal and abnormal mental functioning and personality development, and spawned a new method of psychologically based treatment. Psychoanalysis emerged as a major theoretical underpinning of contemporary “talking cures” (psychotherapies), and its influence spread far beyond treating mental ill-health.

Both world wars profoundly influenced the field. The high incidence of “shell shock” in World War I drove home the lesson that mental illness could affect not only those genetically predisposed, but even the supposedly robust. It soon emerged that anyone exposed to traumatic experiences was vulnerable.

A positive outcome from World War II was the development of techniques for screening large numbers of recruits, which revealed the substantial prevalence of emotional problems among young adults.

The need to treat numerous psychiatric casualties led to the development of group therapies. These paved the way for the so-called therapeutic community, based on the idea that an entire ward of patients could be an integral part of treatment.

The idea of deinstitutionalisation began to gather pace in the 1960s, driven by a burgeoning civil-rights movement. Asylums, an influential book at the time by sociologist Erving Goffman, containing his minute observations of the sense of oppression experienced by patients in these “total institutions”, was one catalyst for their closure.

Hundreds of thousands of long-stay patients began to be transferred to alternative accommodation and specialist care in the community, a process that is still in progress.

What is mental illness?

It is challenging to define what makes a pattern of behaviour and experience a mental disorder. Generally, such a pattern – or “syndrome” – is considered to be a disorder if it is associated with psychological distress, such as intense and prolonged anxiety or sadness, or significant dysfunction, such as a serious impairment in functioning in one or more key areas of daily life.

If the pattern is short-lived, relatively mild, or entirely understandable in light of the trials and tribulations of the person’s life, it should be seen as a problem in living rather than a mental disorder. Such problems may still benefit from consultation with a mental health professional despite not being diagnosable disorders.

This definition of what counts as a mental disorder also clarifies what is not a mental disorder. Merely being unusual or violating social norms does not mean a person has a disorder.

It is difficult sometimes to decide whether a new kind of behaviour is a mental disorder. For instance, should excessive smartphone use or compulsive gambling be counted as diagnosable addictions?

Troubling cases

These decisions about what to include under the umbrella of mental illness are fraught, and there have been some troubling historical cases when disturbing decisions were made or proposed.

In the 1850s, for example, Samuel Cartwright, a physician from Alabama, proposed a new diagnosis called “drapetomania” to explain why African-American slaves would wish to escape their servitude.

He recommended slaves should be treated kindly and humanely to prevent the disorder, but whipped if this treatment failed. A more patent abuse of the concept of mental illness would be hard to imagine, and it should be noted that other physicians ridiculed Cartwright’s proposal at the time.

Two other controversial cases date to the last century. In the early 1970s, one of us (Sidney) stumbled across disturbing media reports that many political and religious dissenters and human-rights activists in the Soviet Union were being labelled as mentally ill and detained in mental hospitals indefinitely or until they renounced their “disturbed ideas”.

For instance, General Pyotr Grigorenko criticised the privileges of the Soviet elite and publicly espoused the rights of the Crimean Tatar ethnic minority group. He was diagnosed with paranoid tendencies, one symptom being his “reformist ideas”, and forcibly committed to a psychiatric facility.

In effect, Soviet psychiatry’s definition of mental illness, and psychosis in particular, was so broad that political beliefs about the desirability of social change were recast as delusions.

The second case comes from the US. Until 1973, homosexuality was defined as a sexual deviation and included in the set of recognised mental disorders. Under pressure from civil, women’s and gay rights activists, it was removed from the diagnostic manual.

Noting such cases, whenever the boundary of a mental illness is expanded to include new diagnoses or loosen old ones, some critics will worry we are treating normal behaviour as a pathology and that we will harm people by labelling them. And whenever the boundary contracts, others will worry that people with psychological troubles are being excluded from clinical care.

Deciding what is and isn’t a mental illness is difficult, but has marked consequences.

This is an edited extract from Troubled Minds: Understanding and treating mental illness by Sidney Bloch and Nick Haslam (Scribe Publications), published 29 August 2023.![]()

Sidney Bloch, Emeritus Professor in Psychiatry, The University of Melbourne and Nick Haslam, Professor of Psychology, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.